In mid-July, Tanya Lokshina, the deputy director for Human Rights Watch’s Moscow office, wrote

that she had received an e-mail from edsnowden@lavabit.com. It

requested that she attend a press conference at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo

International Airport to discuss the N.S.A. leaker’s “situation.” This

was

. Lavabit

,

for instance, that messages stored on the service using asymmetric

encryption, which encrypts incoming e-mails before they’re saved on

Lavabit’s servers, could not even be read by Lavabit itself.

Yesterday, Lavabit went dark. In a cryptic

statement

posted on the Web site, the service’s owner and operator, Ladar

Levison, wrote, “I cannot share my experiences over the last six weeks,

even though I have twice made the appropriate requests.” Those

experiences led him to shut down the service rather than, as he put it,

“become complicit in crimes against the American people.” Lavabit users

reacted with

consumer vitriol

on the company’s Facebook page (“What about our emails?”), but the tide

quickly turned toward government critique. By the end of the night, a

similar service, Silent Circle, also

shut down its encrypted e-mail product,

calling the Lavabit affair the “writing [on] the wall.”

Which secret surveillance scheme is involved in the Lavabit case? The company may have

received a national-security letter,

which is a demand issued by a federal agency (typically the F.B.I.)

that the recipient turn over data about other individuals. These letters

often forbid recipients

from discussing it with anyone. Another possibility is that the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court

may have issued a warrant ordering Lavabit to participate in

ongoing e-mail surveillance. We can’t be completely sure: as Judge Reggie Walton, the presiding judge of the

FISA court,

explained to Senator Patrick Leahy in a letter dated July 29th,

FISA

proceedings, decisions, and legal rationales are typically secret.

America’s surveillance programs are secret, as are the court proceedings

that enable them and the legal rationales that justify them; informed

dissents, like those by Levison or

Senator Ron Wyden,

must be kept secret. The reasons for all this secrecy are also secret.

That some of the secrets are out has not deterred the Obama

Administration from

prosecuting leakers under the Espionage Act for

disclosure of classified information. Call it meta-secrecy.

If Lavabit attempted to resist a

FISA order, the first thing it would have done is petition the

FISA

court to review the order, arguing that it was flawed in some way.

According to some legal commentators, such an argument, no matter how it

is styled,

would almost certainly fail; the

FISA court so frequently

approves surveillance orders that it is often

criticized as a rubber stamp. If Lavabit’s petition failed, it could still drag its feet and force the government to petition the

FISA court to issue an order compelling Lavabit to comply. This would give Lavabit another opportunity to press its case.

If Lavabit lost a petition to compel, and still refused to coöperate,

it could seek review before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court

of Review, which has limited power to review

FISA orders and

is rarely adversarial. According to Judge Walton, only one company has had the chance to

argue before the F.I.S.C.R. as a party objecting to an order—

Yahoo, which initially refused to coöperate with the Prism surveillance dragnet.

If Lavabit lost its appeal to the F.I.S.C.R., and still refused to coöperate,

it would run a serious risk of being found in contempt; that’s how most courts

punish those who disobey its orders. The

FISA court is no different. According to the court’s

rules of procedure, a party may be held in contempt for defying its orders. The secret court may consider many punishments—

secret fines for each day of noncompliance, or even

secret jail time for executives. The idea behind civil contempt is that “

you hold the key to your own cell.”

If you comply, the punishment stops. But hold out long enough and your

contempt may be criminal, and your compliance will not end the jail

sentence or displace the fine.

With these powers, the

FISA court could dismantle a stubborn e-mail service provider, or Facebook, piece by piece. An angry

FISA

court could demand increasingly severe fines, identify more and more

officers for jail time, and make it impossible for Facebook to operate

within the United States by issuing more (and more invasive) warrants.

In this scenario, the

FISA court would order Mark Zuckerberg, hoodie and all, to walk down the hallway to the

FISA court’s

reportedly unmarked

door and explain whether he would coöperate. If he refused to comply,

the court could jail him—and then pressure Sheryl Sandberg, and on down

the line. Aside from the risk of the public finding out its surveillance

methods, the court would only be limited by its willingness to violate

the privacy of Facebook’s users, and inflict pain

on shareholders, who would not have received the

usual disclosures about the company’s books. (In an

HSBC money-laundering case, for instance, afraid of harming the shareholders and

destabilizing the financial system, the government ultimately

blinked, and settled outside of criminal proceedings.)

Because

FISA proceedings are secret, there are only a

few examples of dissent. In 2004, the Internet service provider Calyx

was served with a national-security letter. The letter came with a

gag order, which Calyx’s owner, Nicholas Merrill,

succeeded in getting partially lifted—after more than

six years of litigation. In the meantime, Calyx shut down, with the goal of one day reopening as a

nonprofit Internet service provider focussed on privacy.

In 2007, a former Qwest Communications International executive

(appealing his conviction for insider trading) alleged that the

government revoked opportunities for

hundreds of millions of dollars

of government contracts when Qwest objected to participating in a

warrantless surveillance program. The government refused to comment on

the executive’s allegations. And, finally, Yahoo resisted

FISA orders in 2007 and 2008, according to

published reports and Judge Walton’s letter to Leahy. But Yahoo ultimately

buckled under the threat of contempt. In each case, the resisting company wanted to inform the public, but was initially denied.

Any one company rightly fears the

FISA court’s ability to punish contempt. But the N.S.A.’s surveillance programs are impossible without

robust coöperation

from America’s telecommunications and Internet companies. Silicon

Valley and the telecoms can’t press this leverage because meta-secrecy

keeps the companies trapped in a prisoner’s dilemma. Microsoft doesn’t

know

if Google is heroically resisting.

Tim Cook doesn’t know if Mark Zuckerberg has endured a secret jail

sentence for freedom’s cause. No company wants to be the only one to

disclose its coöperation with Prism and other programs, lest it appear

to be weak on privacy

and set itself at a competitive disadvantage. That’s why Google and other companies

are petitioning

for the right to disclose their participation. And, of course, nobody

wants to be the first public company taken apart in contempt

proceedings.

If Silicon Valley

can coördinate its dissent,

they stand a chance of moving the policy needle. For the government,

meta-secrecy has the added benefit of deflecting the legitimacy that big

business would bring to critics of the surveillance state; the few

known public dissenters are painted as a rogue’s gallery of hackers,

leakers, spies, and traitors. Depending on what he does next, Levison, a

businessman in Texas, could join those ranks.

Levison’s statement provides few clues about what he might do. His mention of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals is

a hint that he was ordered to do something—one of the only ways a case can go directly to a Court of Appeals is to

challenge an agency order. A national-security letter is

one such order,

but there are at least two reasons to think Lavabit was ordered to

participate in ongoing surveillance. First, the strategy of challenging

national-security letters in the district courts has had

some success—why

deviate? Second, Levison described his decision as a choice between

“becom[ing] complicit” and shutting down. One of the few publicly

available national-security letters

demands

that a company not “disable, suspend, lock, cancel, or interrupt

service” until the obligations of the letter are fulfilled. If Levison

was ordered to give up Snowden’s encrypted data, refused, and then shut

down the company, it’s unlikely he’d be going on the offensive in the

Fourth Circuit. And while Lavabit’s encryption and privacy measures make

brute force unattractive, the F.B.I. could have gotten a warrant to

raid Lavabit and seize its hard drives or servers. Shutting down only

mattered if Lavabit’s coöperation did.

There are already two theories as to what a

FISA order against Lavabit may have looked like. First,

FISA could have ordered Lavabit to insert spyware or build

a back door for the N.S.A., as American and Canadian courts

reportedly did to the encrypted e-mail service Hushmail, in 2007. Second,

FISA could have ordered Lavabit to permit the

N.S.A. to intercept users’ passwords. But the truth may never come out.

In a press conference on Friday, President Obama, in addition to

pledging greater transparency surrounding the use of Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which the

government invokes to gather telephone records, promised to work with Congress to improve the

FISA court. He proposed to make its deliberations more transparent and

more adversarial, so that

FISA judges hear from advocates for both “security” and “liberty.” Most important, he committed to establishing public trust in “

the whole elephant” of America’s surveillance programs. That will require open debate—something this Administration has not guaranteed thus far.

Michael Phillips is an associate at a Wall Street litigation firm.

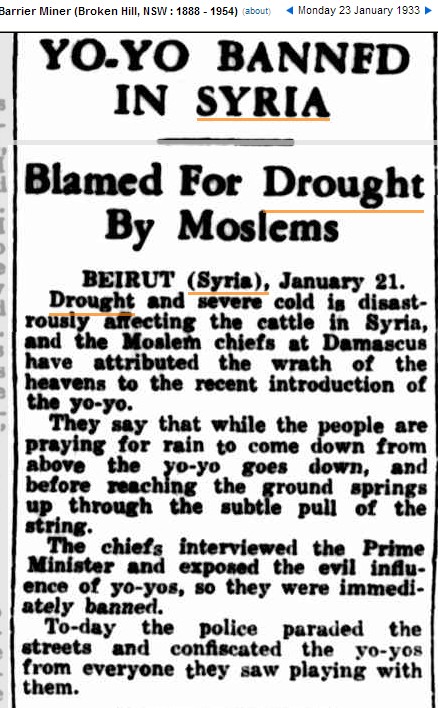

So proud of his war making power, the president has briefed Congress that the FIRST unit of CIA trained rebels is on its way to Syria to undermine the current government. It strikes many as odd that the president never once mentioned any acts of aggression against Coptic Christians, when making his case for military strikes against Syria, only acts committed against muslims.

So proud of his war making power, the president has briefed Congress that the FIRST unit of CIA trained rebels is on its way to Syria to undermine the current government. It strikes many as odd that the president never once mentioned any acts of aggression against Coptic Christians, when making his case for military strikes against Syria, only acts committed against muslims.